This sculpture was constructed at American Steel Studios in Oakland and largely funded by a small honorarium art grant from the Burning Man Festival. Gray Davidson led the project, Colin Leon contributed integral mechanical and artistic design components, Misha Naiman contributed to the visual design and Adrian Coyne, Hugh Wimberly, Bramani Quinn and Jennifer Tarvin worked on the build. Here follow the contents of the original art grant, visions to which the project held true.

Just as we are a sect of homo-sapiens which grows lush in our desert habitat, I like to imagine that everything about our city – the striped tents, the night beacons, the strange crawling vehicles, the unexpected flames – are equally living products of the rare atmosphere of the playa. I think of what creatures might evolve there in the heat and the dust, with the sun and the wind for power, with a peacock’s urges to be admired day and night, with a joy in the solitude and the rough edges of the natural world that spawned them. What might develop as the denizens of the Carnival of Dreams if their constituent molecules were dust and rust and sunlight? The Serpent participates in this vision as a creature that has evolved to take advantage of the special affordances of Burning Man. It is an encouragement to seek beauty from what might otherwise be rough metal and glass, energy from the movement of the wind, and to treat with respect, and perhaps a little fear, those strange entities – human, canvas, metal, plastic, wooden – that make up the city around us.

It is not important to me to create a work which will be visible over the horizon from Gerlach, or whose flame cyclone penis lights the sky in Cedarville. But I do want to create a work which will capture the imaginations of those who look at it, which will draw them into its world, and make them feel, for a few instants of contemplation, that they are not the only conscious, highly evolved beings in the dust.

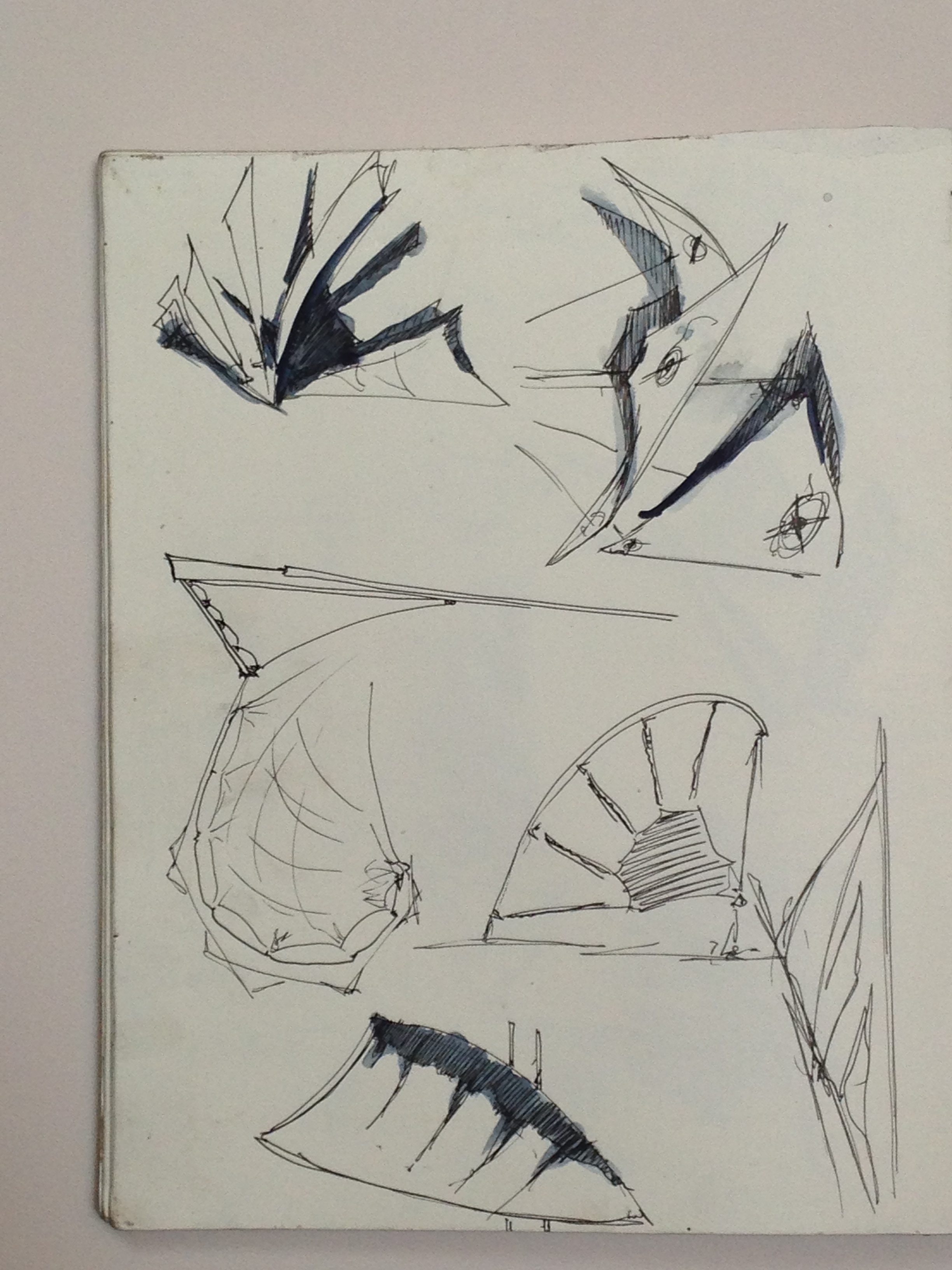

The Serpent is a perfectly balanced mobile formed of a series of bent-metal pipes which each carry a segment of the serpent’s body. A lateral motive force on the lead segment can create a wave-like motion through the entire body. Flames rise from the spine of each segment like a mane of fire along the serpent’s back. The external structure of each segment will form the counterweight that holds up the remaining segments.

A strong armature (from segments of 4” pipe) will form a stable base for the sculpture and allow it to hang freely and safely in the air. This armature will be braced out in all directions by metal pipes which will be buried 2” into the playa. These will also be pinned into the playa with 36” stakes. Each stake will be protected with soft objects, such as tennis balls at its tip, and marked at night with solar powered LED lights.

The serpent’s ‘bone structure’ will be a series of eight arcs of 1”X1” square pipe, invisible from the outside. These will connect one to another by linked eye-bolts. The bolts will impose a maximum angle of swing to each side, thus determining the maximum curvature of the spine when assembled.

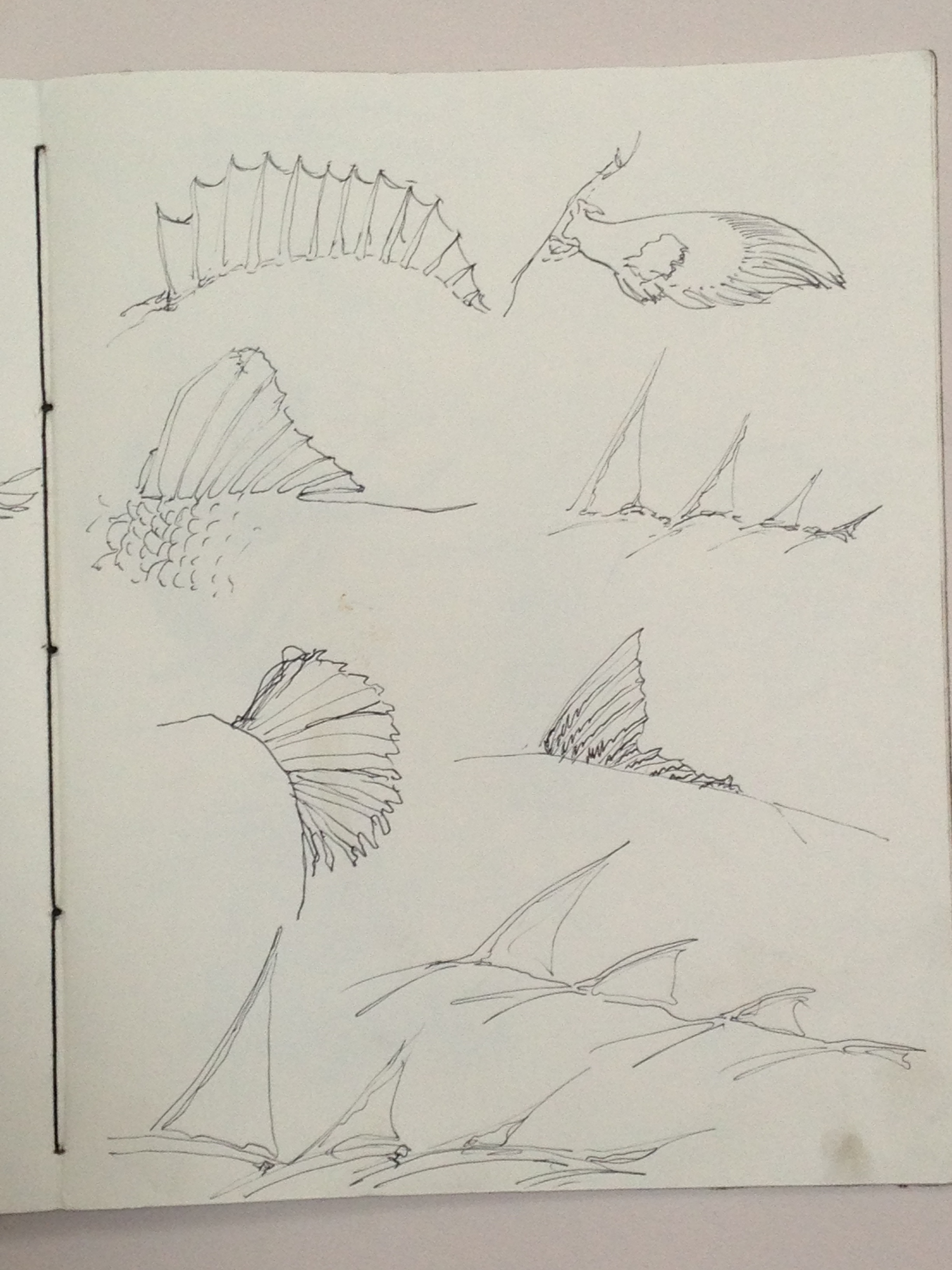

The external, visible structure will be built from thin aluminum, which will be cut and bent into the desired elegant shapes to outline the body of the serpent. These shapes will be riveted together and to the steel bone structure within. There is room for a lot of creativity here, especially since the aluminum skin is not meant to block all eyesight into the body. I want participants to be able to see transparently how the entire sculpture has been built, and so the panels of aluminum will be cut into many smaller, irregularly woven panels which create the form of the body.

Simple rubber LPG fuel lines will run through the armature and down the chain to the sculpture, splitting at each body segment into an open flame and a further fuel line, leading to the next segment. These fuel lines will be made from flexible rubber hose to avoid hampering the sculpture’s movement. Regulated flames will rise from within the head, and from the spine of each body segment. There will be no ‘poofing’ flame effects. Flame effects are planned to be about 8 inches tall.

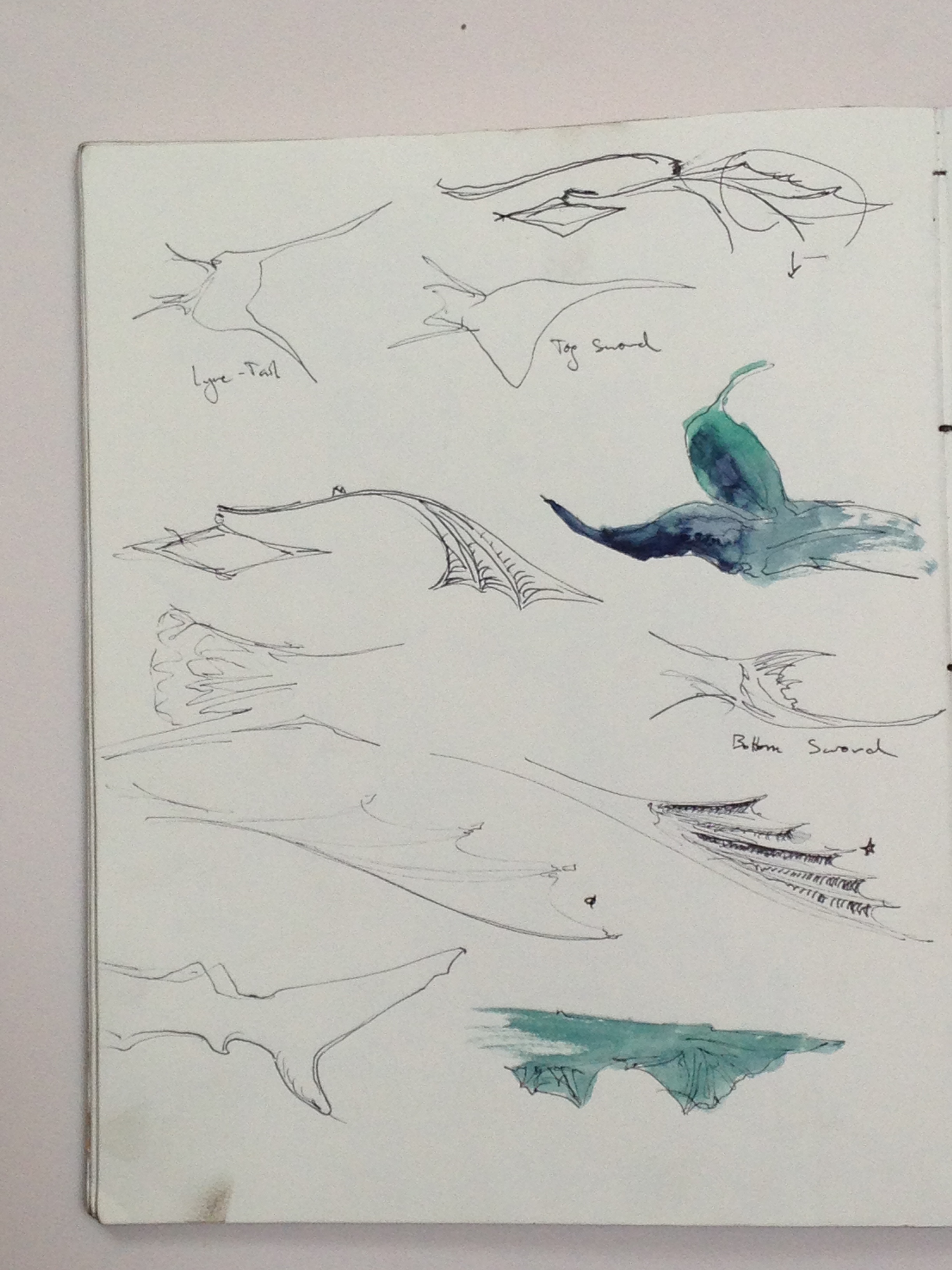

The primary sail will be a metal frame, hanging below the serpent’s head like the beards of Eastern dragons. It will be stretched with canvas sailcloth which will be sewn with grommets and hammed so as not to tear in the playa winds. By allowing the sail to rotate laterally, with its center of area ahead of its center of mass with respect to the wind, it will cause the head (and therefore the whole mobile) to swim back and forth through the air. Smaller sails will provide visual effect on the sides of the body like wings, and will cause a less systematic, but similar movement effect vertically. Canvas sailcloth and flame effects will always be separated by several feet of distance.

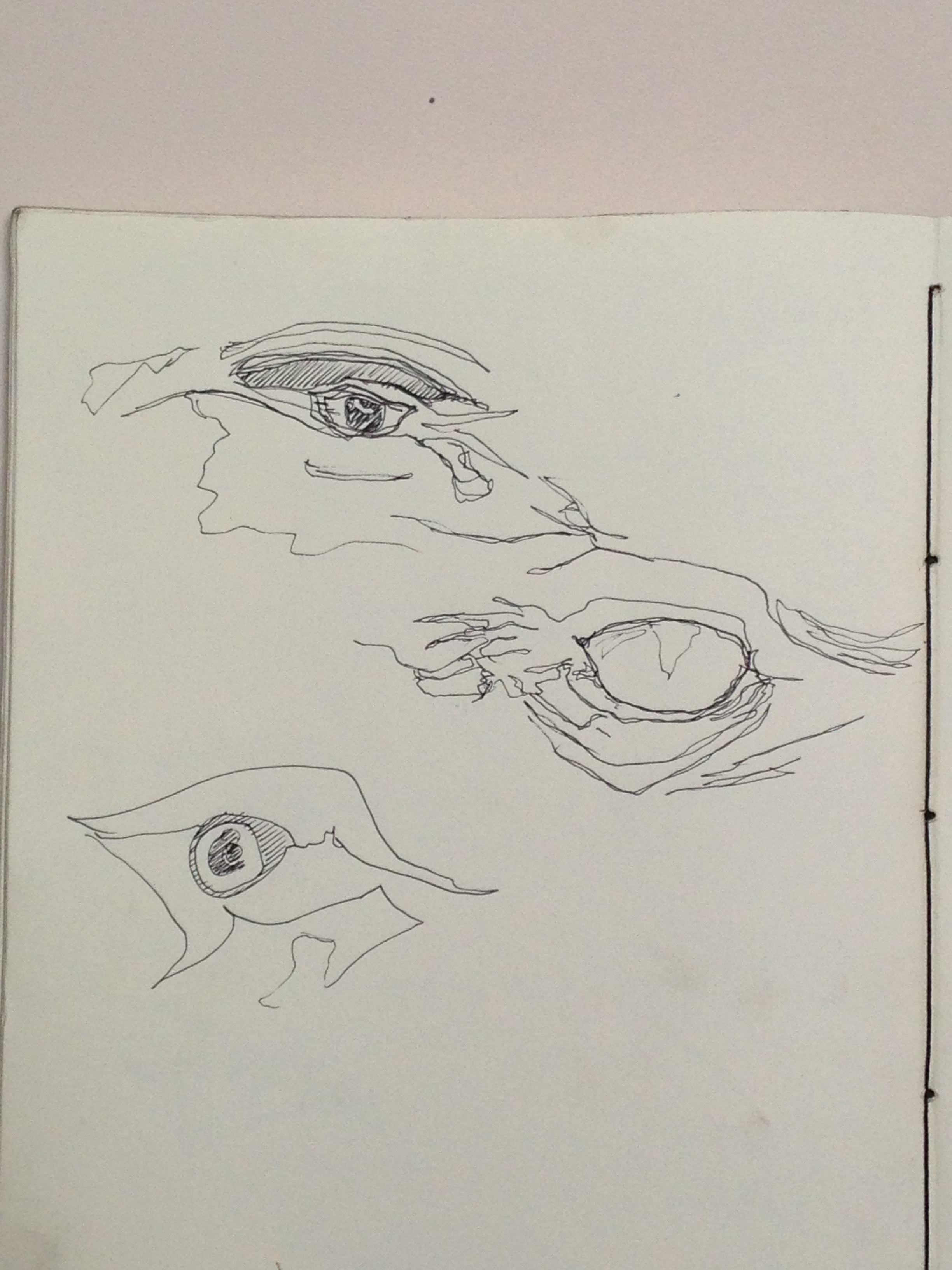

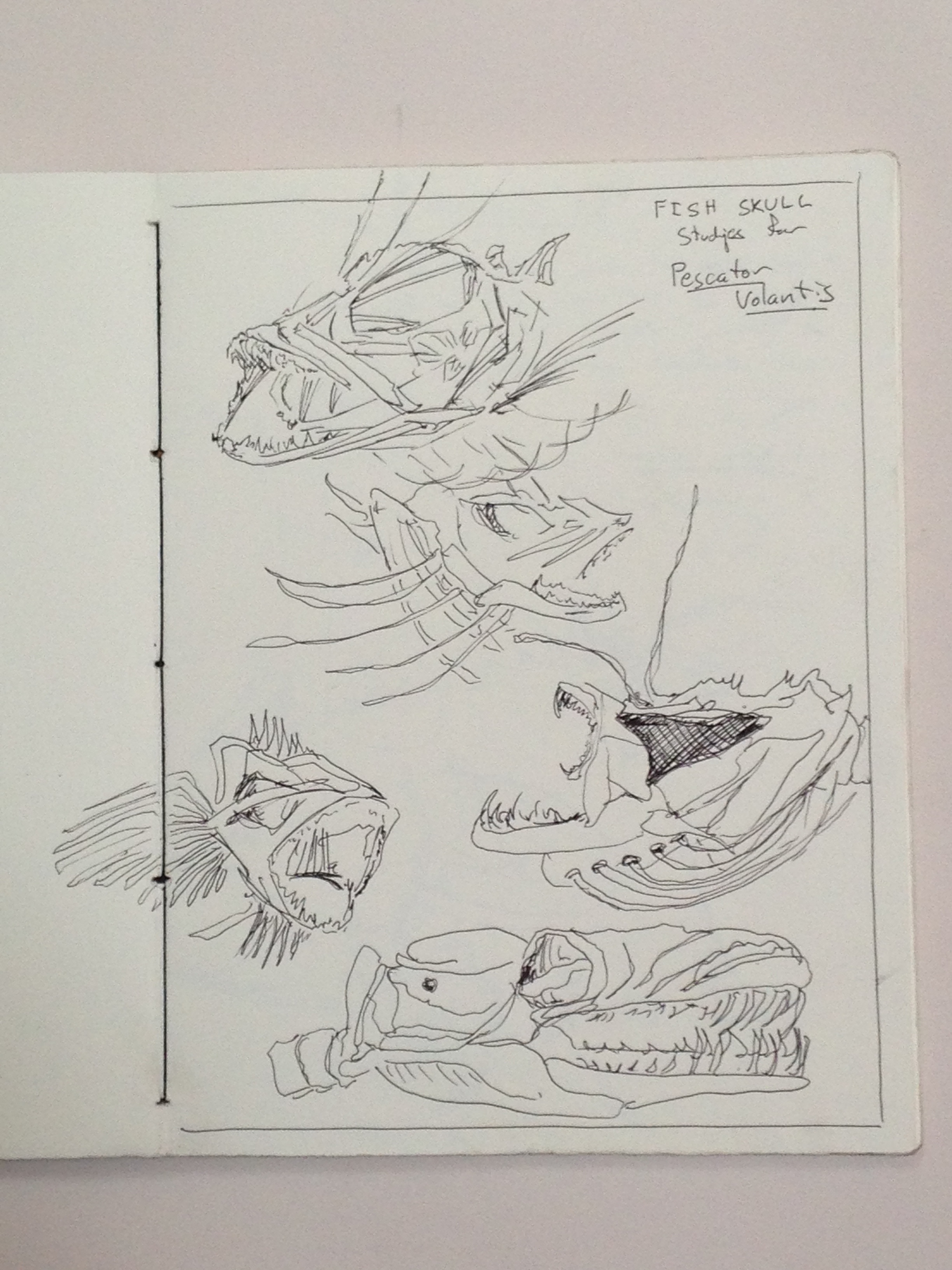

The head will be built from glass panes, soldered together. Most of these panes will be clear glass but some may be made from colored glass as well. The fire inside the head will shine through these panes making the sculpture a beacon at night. Shifting the material from aluminum to glass in the head will give us greater control over the design of and emotion in the head. The head is intended to be perceived as watchful and intent and possibly dangerous, as though its jaws might snap open and closed at any moment.

The Dancing Serpent’s purpose is to remind participants to interact with works of art as though with conscious beings. Art should not be present to be ‘taken in’ or to be looked at, but is to be respected, trusted, intimidated by and learned from. The idea that art is conscious is integral here, as we allow ourselves to be inspired by works which are no longer ‘what’ but are ‘who’ such as Marco Cochran’s Bliss, Pier Group’s Ichthyosaur and FLG’s Soma. Works such as these have so much strangeness and personality that they cannot but be met on their own terms. This is the goal of the Serpent, to thin the barriers between observer and artwork and between reality and fairy tale.

Here we explore what might evolve in the Black Rock Desert if its constituent molecules of rusted railroad ties, dust, sunlight and wind were to mate and spawn a predatory creature. The serpent hangs intentionally in midair, at eye level, so that passing humans look it in the eyes or in the jaws, and contemplate it as an entity they are unfamiliar with, but which has just as much – perhaps more – right to be there in that desert as they do.